A parallel runtime library for executing concurrent directed acyclic graphs of computational tasks with a focus on a very low-overhead when executing micro-tasks, speed, portability, light weight, and user friendly interface

See full documentation here (https://tasktorrent.readthedocs.io/en/latest/).

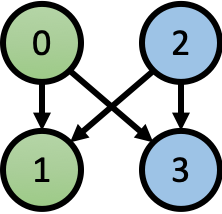

In this short tutorial, we explain the main features of TaskTorrent through a simple example with 4 tasks distributed on 2 ranks. The complete code can be found here, along with an example Makefile. The following picture shows the dependencies between tasks

Rank 0 should run task 0 and 1, while rank 1 should run task 2 and 3. This is not a typical graph of tasks from a scientific code but it illustrates the main functionalities of c.

This system uses the parametrized task graph model.1,2 As such, tasks are described by an index K (typically an int, tuple of int, or pointers). In this example, we will use int. Tasks 0 and 2 can run immediately since they have no dependencies. However, when they finish, they both need to trigger tasks 1 and 3. While some dependencies are "local", some are remote (i.e., on other ranks). This is handled using remote procedure calls.

The basic philosophy behind TaskTorrent is MPI + X. The complete DAG is distributed across nodes by the user. Each node is assumed to be a shared memory computer. On each node, the calculation is described as a local DAG (directed acyclic graph), with dependencies. A thread pool is created. The number of threads is typically set equal to the number of cores on the node. A scheduler is in charge of managing dependencies between tasks and assigning tasks that are ready to run (all dependencies are satisfied) to worker threads. The execution is somewhat similar to the concept of task in OpenMP. However, the runtime is more general as it can handle arbitrary graphs with complex dependencies. The current backend to manage threads is C++ threads.

Nodes communicate through active messages. These are messages that contain data and a function that will be run on the remote node following the reception of the data. All this is not exposed to the user the library is handling the communication through MPI, using non-blocking send and receive. The main thread that starts the program is handling all the MPI requests (which are therefore processed sequentially). This follows the concept of MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED. That is we are running a multithreaded code, but only the (main) thread that calls MPI_Init_thread makes subsequent MPI calls. See for example MPI_init_thread or similar page.

But let's start with a simple example to illustrate the syntax and logic of TaskTorrent.

- First, we begin with some basic MPI-like information

const int rank = comm_rank();

const int n_ranks = comm_size();

if (n_ranks < 2)

{

printf("You need to run this with at least 2 ranks\n");

exit(0);

}

printf("Rank %d hello from %s\n", rank, processor_name().c_str());- Then, referring to each task by an integer from 0 to 3, we declare some information regarding their dependencies

// Number of tasks

int n_tasks_per_rank = 2;

// Outgoing dependencies for each task

map<int, vector<int>> out_deps;

out_deps[0] = {1, 3}; // Task 0 fulfills task 1 and 3

out_deps[2] = {1, 3}; // Task 2 fulfills task 1 and 3

// Number of incoming dependencies for each task

map<int, int> indegree;

indegree[0] = 1;

indegree[1] = 2;

indegree[2] = 1;

indegree[3] = 2;This is not in general how dependencies would be computed since this approach does not scale to very large problems, i.e., when the number of tasks is very large. But, in this example, we use this approach to explicitly demonstrate the basic concepts.

Note that node 0 and 2 are listed as having 1 dependency. This is because they need to be started or "seeded" by the main thread. This is done by calling tf.fulfill_promise(0 /* or 2 */) as shown below. All tasks are therefore started either: by other tasks, or by the main thread when the computation starts. The indegree for all tasks that need to be run must be greater or equal to 1 as a result.

- We then create a function mapping tasks to ranks

// Map tasks to rank

auto task_2_rank = [&](int k) {

return k / n_tasks_per_rank;

};- We create a thread pool, a task flow and a communicator structure:

// Initialize the communicator structure

Communicator comm(MPI_COMM_WORLD, verb);

// Initialize the runtime structures

Threadpool tp(n_threads, &comm, verb, "WkTuto_" + to_string(rank) + "_");

Taskflow<int> tf(&tp, verb);Threadpool() takes arguments describing how many threads to run. verb sets the verbosity level for information messages. The string at the end is used for profiling and logging. In the library, the thread pool consists in n_threads C++ threads that are created when calling tp.start(), and live until tp.join() is called at the end.

The task flow tf needs to point to the thread pool &tp that will be executing the tasks the local node.

- We create a remote procedure call. This registers a function that will be executed on the receiving rank using the provided arguments, which are sent over the network using MPI (the MPI calls are all made by the TaskTorrent library). All MPI send and receive calls made by the library are non-blocking.

// Create active message

auto am = comm.make_active_msg(

[&](int &k, int &k_) {

printf("Task %d fulfilling %d (remote)\n", k, k_);

tf.fulfill_promise(k_);

});The local structure tf is accessed by reference capture ([&]). Note that since this function is run on the remote node, in this call, we need to understand that tf refers to the variable tf on the remote node, not on the local node that issues the active message.

- We declare the tasks using a parametrized task-graph model.

// Define the task flow

tf.set_task([&](int k) {

printf("Task %d is now running on rank %d\n", k, comm_rank());

})

.set_fulfill([&](int k) {

for (int k_ : out_deps[k]) // Looping through all outgoing dependency edges

{

int dest = task_2_rank(k_); // defined above

if (dest == rank)

{

tf.fulfill_promise(k_);

printf("Task %d fulfilling local task %d on rank %d\n", k, k_, comm_rank());

}

else

{

// Satisfy remote task

// Send k and k_ to rank dest using an MPI non-blocking send.

// The type of k and k_ must match the declaration of am above.

am->send(dest, k, k_);

}

}

})

.set_indegree([&](int k) {

return indegree[k];

})

.set_mapping([&](int k) {

/* This is the index of the thread that will get assigned to run this task.

* Tasks can in general be stolen (i.e., migrate) by other threads, when idle.

* The optional set_binding function below determines whether task k

* is migratable or not.

*/

return (k % n_threads);

})

.set_binding([&](int k) {

return false;

/* false == task can be migrated between worker threads [default value].

* true == task is bound to the thread selected by set_mapping.

* This function is optional. The library assumes false if this

* function is not defined.

*/

})

.set_name([&](int k) { // This is a string used for debugging and profiling

return "tutoTask_" + to_string(k) + "_" + to_string(rank);

});Tasks need to define at least three functions, by calling (K is the template argument of Taskflow and is an int in this example):

set_task(fun)wherefunis avoid(K)function; this is the function the task will execute;set_indegree(fun)wherefunis anint(K)function, indicating the number of incoming dependencies of the task;set_mapping(fun)wherefunis anint(K)function, describing on which thread the task is expected to run. Note that, generally, tasks can be migrated between threads for load-balancing.

Note that if indegree for a task is not equal to the number of incoming edges in the DAG, then the program will not execute properly. This is a bug. If indegree is too small, the behavior is unspecified (the code may run to completion, an error message may be thrown, or the task will be run twice). If the indegree is too large, the task will never run but the threads will return at join() without executing all the tasks in the DAG (see below for join()).

The following functions may be defining optionally:

set_fulfill(fun)wherefunis avoid(K)function; this is used to specify which dependencies are satisfied. The functionfulfillis run right after the functiontaskso there is some freedom to move code betweentaskandfulfill. The reason to havefulfillis for the user to make a clear distinction in the code between the computational task and the management of dependencies.set_binding(fun)wherefunis abool(K)function; each task is mapped to a thread usingset_mapping. Mapping will determine how a task is initially assigned to a thread. However, by default tasks are allowed to migrate between threads (task stealing). This can be disabled by setting binding to true (i.e.,set_bindingreturnstruefor that task index). In that case, the task is guaranteed to run on the thread defined bymapping. This is useful when different tasks try to update the same variable, for example when doing a reduction. In that case, there is a race condition in parallel. However, if all these tasks are assigned to the same thread andbindingis set to true, the race condition is avoided. This is a little bit similar (although not identical) to the critical clause in OpenMP.set_name(fun)wherefunis astring(K)function, returning a string that describes the task (useful for logging, profiling and debugging).set_priority(fun)wherefunis adouble(K)function, returning the priority of the task. Higher priority tasks are run first. The default priority is 0.

The line am->send(dest, k, k_) sends the data from the remote rank to rank dest. The data being sent are two integers, k, and k_. Arbitrary data can be included in am->send. The types of these data must match the declaration of the active message:

auto am = comm.make_active_msg(

[&](int &k, int &k_) {

...

});The variables k and k_ in am->send(dest, k, k_) correspond to the arguments [&](int &k, int &k_) in the lambda function above. The library will take variables k and k_ on the remote rank, send the data over the network to rank dest, and call the active message using these data on rank dest. Note that the lambda function associated with the active message

[&](int &k, int &k_) {...}is run by the main thread of the program through the comm object defined previously. Worker threads that compute the DAG tasks are not involved in processing active messages. Consequently, TaskTorrent assumes that relatively few flops need to be performed in each active message since limited computational resources are assigned to running them.

The active message can be used to fulfill dependencies but can also be used for any other operations. The active messages are always run by the main thread (the one running main() in the program). No race condition can therefore exist between different active messages. However, since tasks in task flows are run by worker threads, race conditions must be avoided between tasks in task flows and active messages.

It is possible to use am->send(dest, k, k_) for a processor to send a message to itself (i.e., dest == this_processor_rank). This may be useful in some rare cases. It is in general more efficient to simply run a function using the current worker thread. For example, in this program we simply call tf.fulfill_promise(k_) on the current rank.

However, calling am->send(dest, k, k_) can simplify the code since we do not have to distinguish whether dest is the local or a remote processor. In both cases, we can simply call m->send(dest, k, k_). For example, a piece code equivalent to the one above would be:

[...]

.set_fulfill([&](int k) {

for (int k_ : out_deps[k]) // outgoing dependency edges

{

int dest = task_2_rank(k_);

am->send(dest, k, k_);

}

}

[...]There are also cases where it is advantageous to run this code using am->send and an active message. In that case, no message is actually sent. Instead the main program thread uses the data provided in am->send and runs the active message on the local processor. Note that this is not visible to the user. The comm object is responsible for this. The main difference is therefore that the body of the active message (in this example tf.fulfill_promise(k_)) is run by the main program thread, which is in charge of the MPI communications (using the comm object), instead of a worker thread. This is a small difference but it is important when, for example, a reduction is performed inside the active message, for example x += .... Consider the following fictitious example:

int x;

auto am = comm.make_active_msg(

[&](int &k_) {

x += k_;

});

// Define the task flow

tf.set_task([&](int k) {})

.set_fulfill([&](int k) {

for (int k_ : out_deps[k]) // Looping through all outgoing dependency edges

{

int dest = task_2_rank(k_); // defined above

if (dest == rank)

{

x += k_;

}

else

{

am->send(dest, k_);

}

}

})

.set_indegree([&](int k) {

return indegree[k];

})

.set_mapping([&](int k) {

return (k % n_threads);

});This code has a race condition because the main thread running the active message performs an update on x while a worker thread may concurrently do the same thing. However, if both operations are done through an active message, all x updates are done using the same thread (the main program thread) and therefore the race condition is eliminated.

The following code no longer has a race condition because all x updates are done through an active message:

int x;

auto am = comm.make_active_msg(

[&](int &k_) {

x += k_;

});

// Define the task flow

tf.set_task([&](int k) {})

.set_fulfill([&](int k) {

for (int k_ : out_deps[k]) // Looping through all outgoing dependency edges

{

int dest = task_2_rank(k_); // defined above

am->send(dest, k_);

}

})

.set_indegree([&](int k) {

return indegree[k];

})

.set_mapping([&](int k) {

return (k % n_threads);

});In conclusion, this example shows that, in some rare cases, it may be useful to use active messages even to run a task on the local processor.

- Finally, the initial tasks are "seeded" (i.e., started and sent for execution to the thread pool). The threads will run until: (1) all tasks in the DAG (the direct acyclic graph that defines all the tasks and their dependencies) have been executed, (2) and all communications are complete (i.e., the non-blocking MPI send and receive are complete). Both conditions need to be satisfied globally, across all nodes, before the threads can return.

// Seed initial tasks

if (rank == task_2_rank(0))

{

tf.fulfill_promise(0); // Task 0 starts on rank 0

}

else if (rank == task_2_rank(2))

{

tf.fulfill_promise(2); // Task 2 starts on rank 1

}Then run until completion:

tp.join();The function join() is similar to the C++ join() function and will block until all worker threads return. join() contains a synchronization point across all nodes. Note that this synchronization point exists before the threads actually return. To be specific, this synchronization point occurs when rank 0 notifies all threads across all nodes that the DAG has been completely executed. The synchronization point does not occur after the threads return. Consequently, in some cases, it may be useful to add MPI_Barrier() after join() if one needs to make sure all threads have returned on all nodes before proceeding with the rest of the program execution.

The previous examples demonstrate how to send C++ objects using active messages. Be careful that only the data contained in the object is sent over the network. For example, data "associated with" a pointer are not sent. Consider this class:

class my_vector {

public:

double * p;

int s;

};When sending my_vector v using an active message, the value of the pointer p and integer s are sent (by copying their byte representation). This is probably an error since the user in that case probably intends to send the content of the memory ranging from p to p + s-1. Similarly, sending C++ containers (vector, array, list, etc) is probably an error since only the byte content of the object is sent, not the data "pointed to" by the container.

When one wants to send data associated with a contiguous memory space, for example to send an array or a vector containing data, a special type called views should be used. views allow providing a pointer p and integer size s; the active message will then send all the data from p[0] to p[s-1]. Here is example of the syntax to use.

This is the code to use inside a task to send a view:

auto vector_view = view<double>(p, s);

am->send(dest, vector_view);The active message declaration looks like this:

auto am = comm.make_active_msg(

[&](view<double> &vector_view) {

/*

Use vector_view.data() and vector_view.size()

to use the data stored in the view.

*/

double * p = /* pointer where data will be used on the remote processor */;

memcpy(p, vector_view.data(), vector_view.size() * sizeof(double));

/* rest of code ... */

});When sending active messages (created as auto am = comm.make_active_msg(fun) and sent as am->send(dest, ps...)), any input buffer is temporarily copied by TaskTorrent.

If buffers are large, this may slow down the executing significantly. TaskTorrent provides an alternative using "large active messages"

auto am = comm.make_large_active_msg(fulfill, buffer, release)where fulfill is a void(Ps&...) function, buffer is a (T*)(Ps&...) function and release is a void(Ps&...) function.

The active message can then be sent by

am->send_large(dest, view, ps...)where view is a view<T> pointing to a buffer to be sent.

The three functions are the following:

fulfillis run on the receiver when the buffer has arrived and is ready to be used. Typically this would fulfill some tasks;bufferis run on the receiver and should return a pointer to an allocated buffer sufficiently large to hold the sent buffer;releaseis run on the sender after the buffer has been sent and can be safely reused. This could be used to free the buffer for instance.

The tutorial tutorial/tuto_large_am.cpp provides an example of use of large active messages.

The communication layer uses MPI. Since the code is multithreaded, the code requires MPI_THREAD_FUNELLED. This means that, in the runtime library, only the main thread makes MPI calls (i.e., all MPI calls are funneled to the main thread). So you need to initialize like this

int req = MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED;

int prov = -1;

MPI_Init_thread(NULL, NULL, req, &prov);

assert(prov == req); // this line is optionalSee for example MPI_Init_thread for some documentation on this point.

To build this example, you will need

- A C++14 compiler (C++ compiler support).

- An MPI implementation (see the MPI Forum for MPI documentation). There are many options: MPICH, MVAPICH, Open MPI, Cray MPICH, Intel MPI, IBM Spectrum MPI, Microsoft MPI

- On MacOS/Linux, you can also use Homebrew. For instance, to install MPICH:

brew install mpich

- On MacOS/Linux, you can also use Homebrew. For instance, to install MPICH:

- If you are running on a single node only, and do not use MPI for communication, you can compile the code with the option

-DTTOR_SHARED. This will comment out the components of the library that depend on MPI. You can then compile the code with a standard C++ compiler instead of mpicxx for example. - The code contains a lot of assert statements. In production/benchmark runs, we recommend compiling with the option -DNDEBUG. This will disable all the assert checks. This doesn't disable MPI error checking ; those are always checked.

Once you have this:

- First, navigate to the

tutorialfolder

cd tutorial- Build the example. This assumes that mpicxx is a valid MPI/C++ compiler.

make- Run the example, using 2 MPI ranks. This assumes that mpirun is your MPI-wrapper.

mpirun -n 2 ./tuto- In general, it is safer to create a task with some given index

konly once during the calculation. It is possible to have a task show up in the DAG multiple times. However, for correctness, the dependencies of an occurrence ofkmust be all satisfied before the "next" task with indexkgets created again (through a call tofulfill_promise(k)). This is potentially error prone, maybe a source of confusion, and should be avoided. We therefore recommend that a task with indexkbe created only once throughout the calculation. - The code will always check MPI return codes and abort if any MPI function return anything else than

MPI_SUCCESS.

Documentation can be built using Sphinx and Doxygen.

In short, with Doxygen and Sphinx installed, move to the docs/ directory and run something like

doxygen && sphinx-build . sphinx_html -Dbreathe_projects.TaskTorrent=doxygen_output/xml

It is also accessible online at https://tasktorrent.readthedocs.io

1 Automatic Coarse-Grained Parallelization Techniques, M. Cosnard, E. Jeannot ↩

2 Automatic task graph generation techniques, M. Cosnard, M. Loi ↩